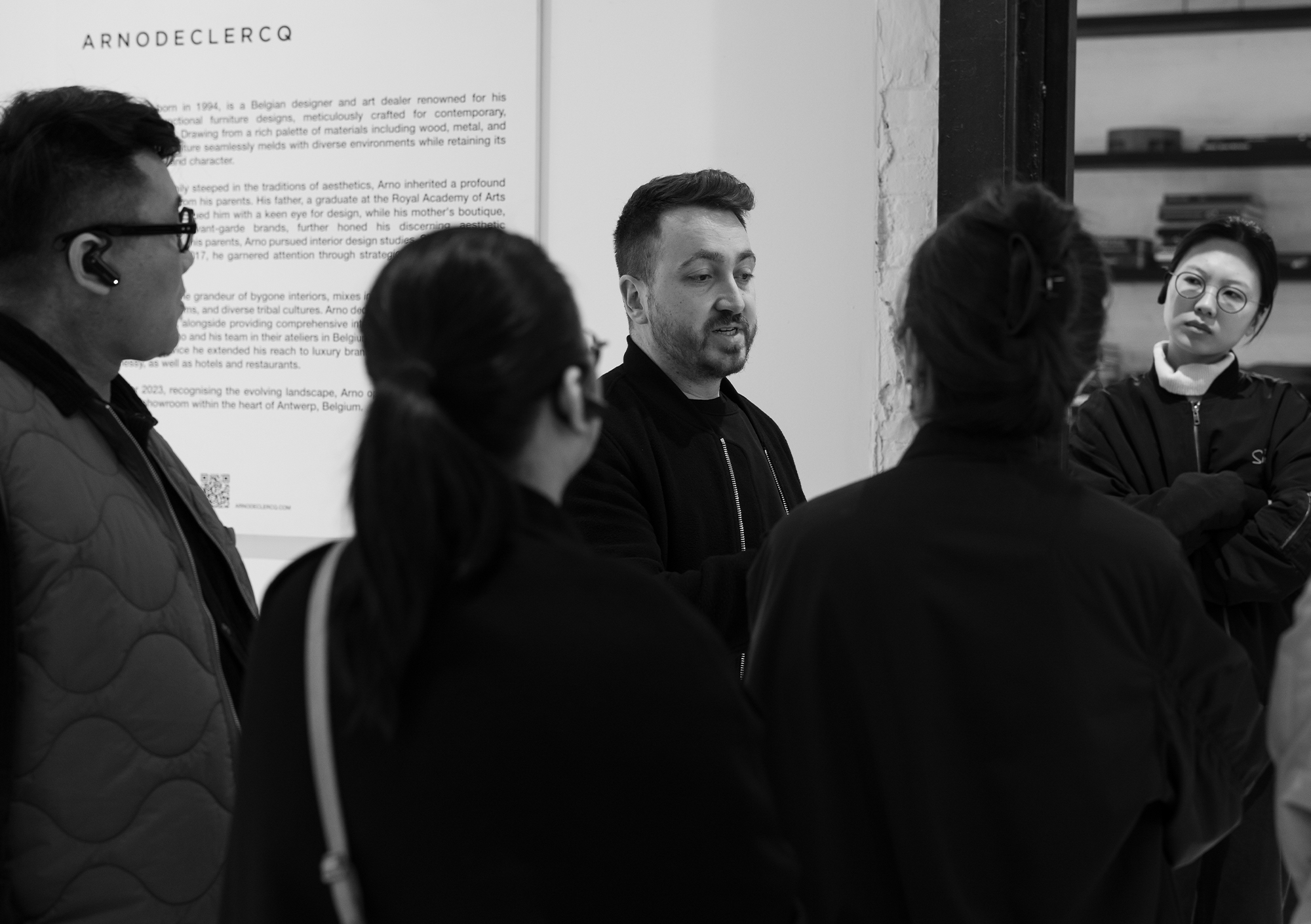

Tucked quietly into the rhythmic cityscape of Antwerp, Arno Declercq’s studio doesn’t announce itself with grandeur. It doesn’t need to. What lies within is not a showroom, but a living archive—a spatial autobiography written in wood, metal, fire, and time. This is where Arno Declercq welcomed us during our design and art tour through Belgium, guiding us into a world shaped by hands, intuition, and an unwavering belief in form.

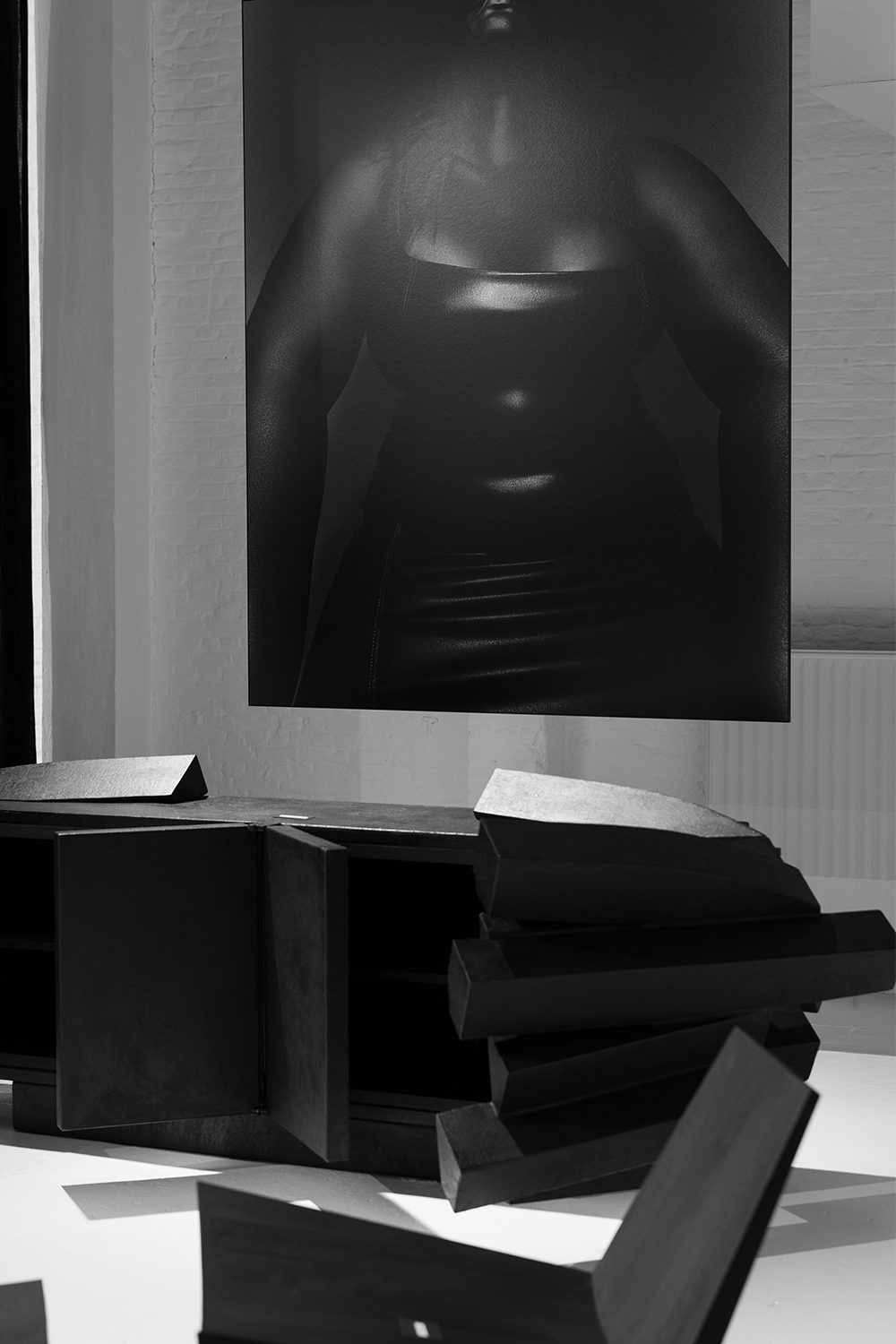

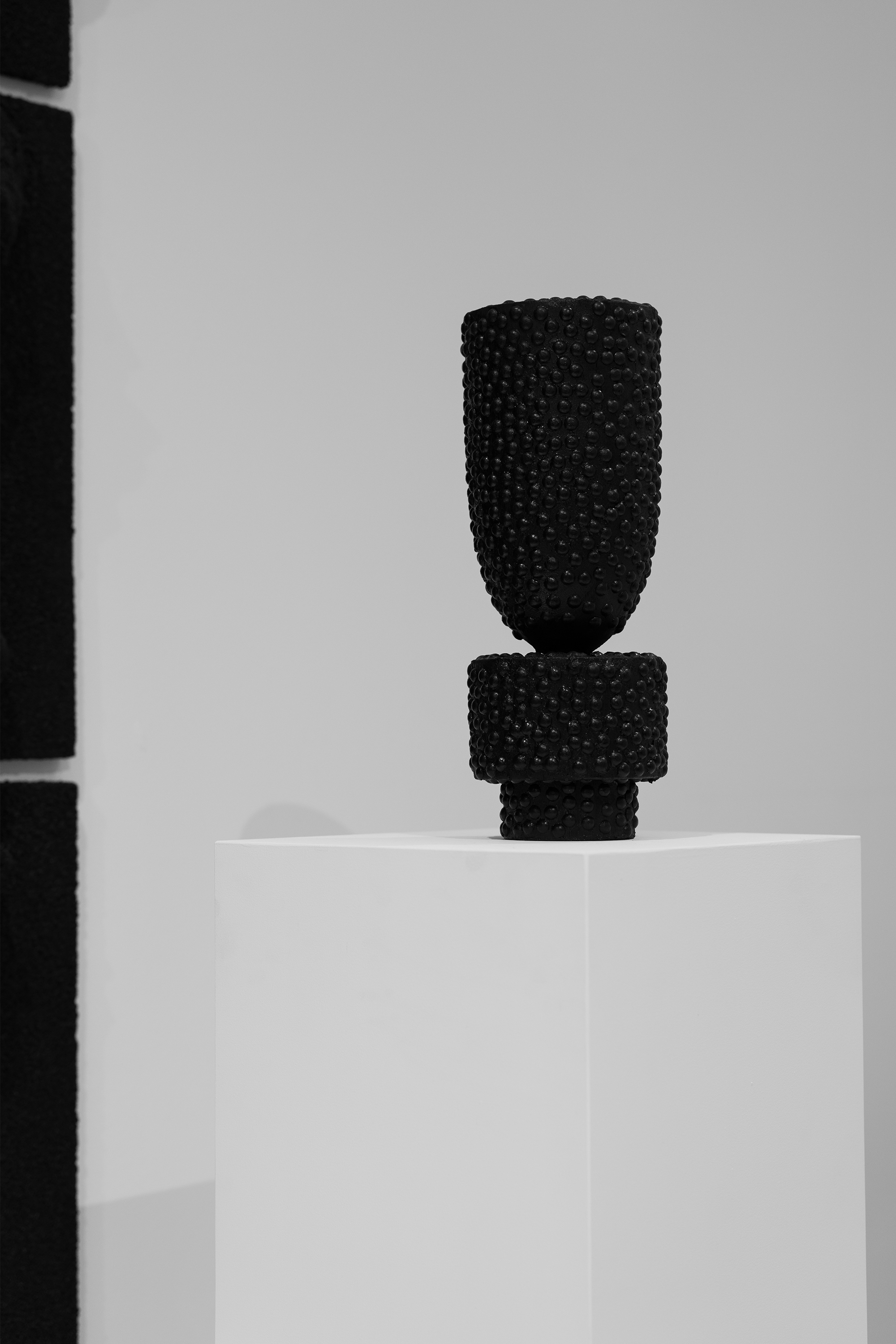

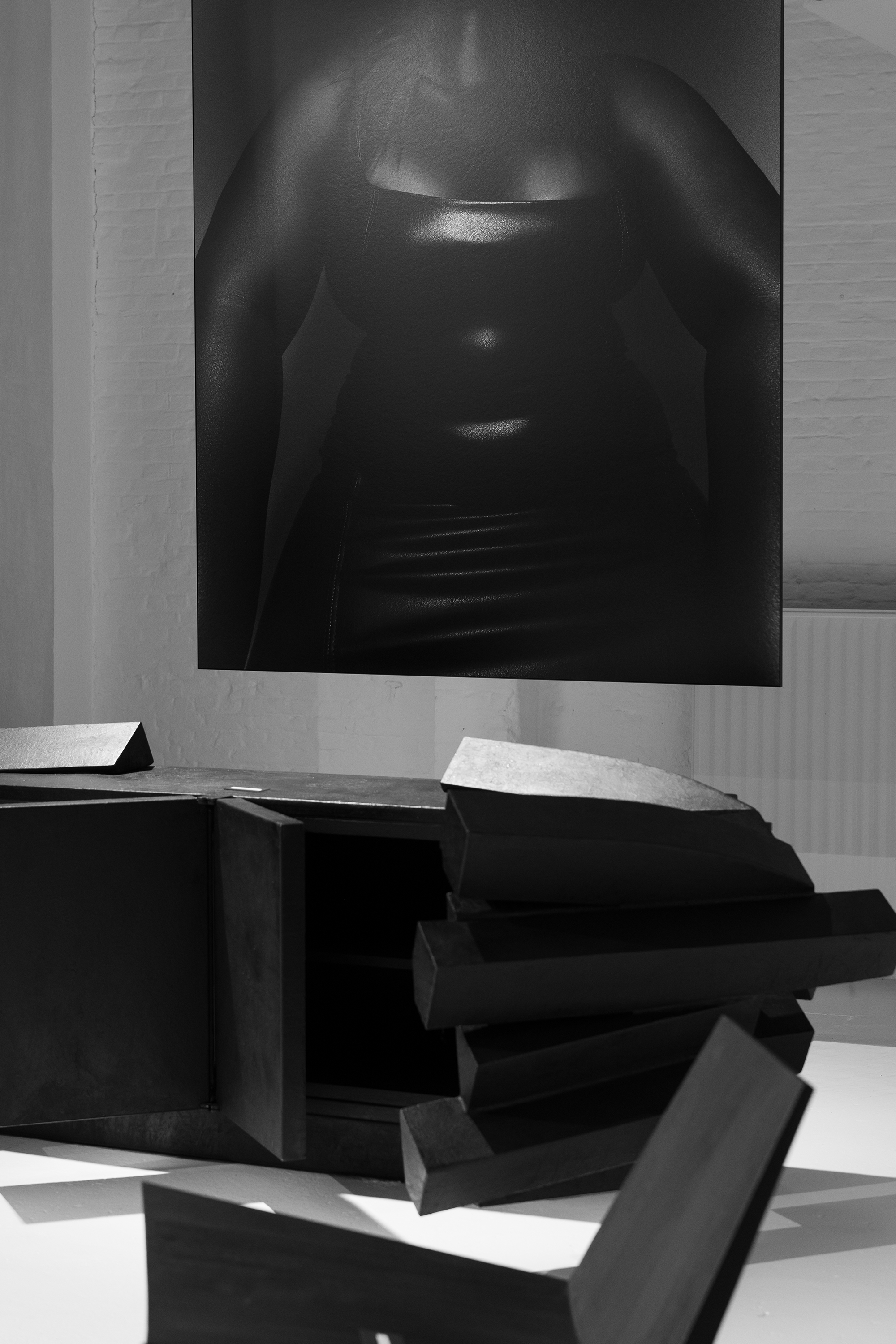

Arno Declercq is a Belgian designer and art dealer known for his sculptural, bespoke objects that merge primitive form with contemporary refinement. With a background in interior design and ethnographic curation, he launched his own line in 2017, drawing influence from tribal art, ancient architecture, and military structures. His pieces, handcrafted from Iroko and Belgian oak, are finished using the traditional Japanese technique of Shou Sugi Ban, creating a charred surface that enhances both durability and texture.

Declercq doesn’t hide behind design language. He speaks plainly, but with the confidence of someone who’s burned—literally—through hundreds of hours of wood and metal to develop his signature. He is a self-taught maker, driven by curiosity, not trend. “I never studied woodwork,” he told us. “I learned everything myself. No money, no tools. I made my own.” It’s not a romantic beginning, but a raw one. Yet from those modest origins, he has cultivated a language of design that now speaks fluently to luxury brands, world-class architects, and collectors from Los Angeles to Shanghai. Today, his work is represented by over 20 galleries worldwide.