- ARCHITECTURE

- Atelier Carle

- INTERIOR

- Atelier Carle

- LANDSCAPE

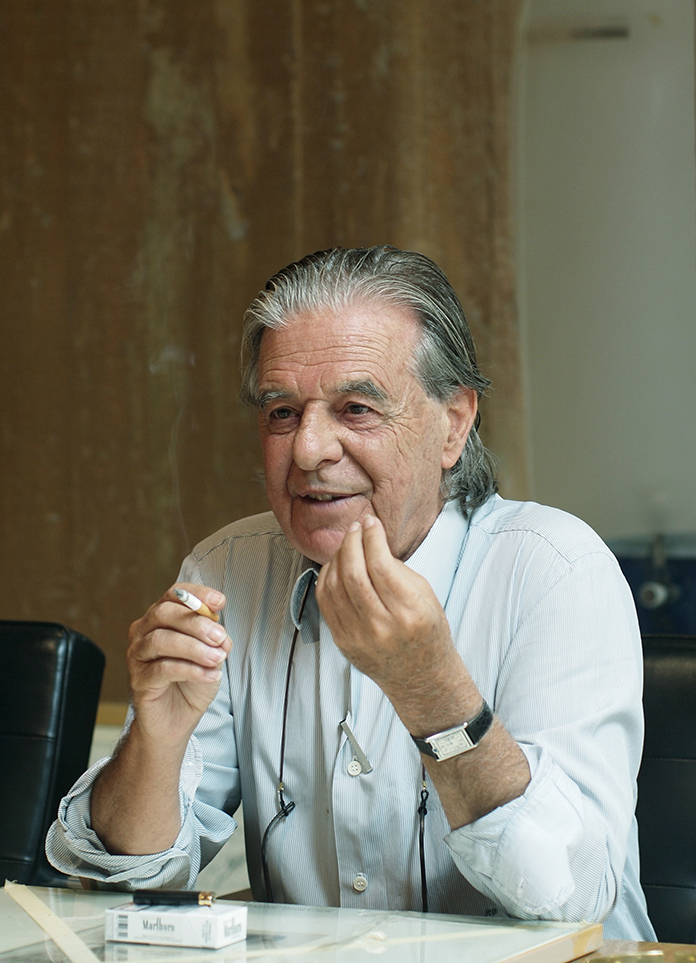

- Oscar Hacche

- PHOTOGRAPHY

- Alex Lesage

- EDITOR

- Jinjie

In the southern region of Brome-Missisquoi, Quebec, the BROM residence sits in a landscape that speaks quietly, yet carries the weight of time. What remains of late 19th-century vernacular architecture in this area lends the site a distinct cultural density. On this land where history and nature converge, Atelier Carle chose to intervene with a sense of restraint—through what they describe as a practice of common work—to respond to the evolving legacy of rural architecture in a contemporary context.

In this conversation with the team at Atelier Carle, Yinjispace explored their understanding of “cultural consensus,” their stance toward elements that can no longer be preserved, and how architecture might respond to a site’s memory through material and spatial continuity rather than rewriting it.As they emphasized during our exchange:“When the original structure can no longer be preserved, we must assume a duty of remembrance. Culture—and architecture in particular—is always part of an ongoing narrative that integrates the past, the present, and the future.”

The scale of the occupancy program desired by the client, combined with the deterioration of the existing building (a wooden structure from the early 20th century with rubble stone walls), necessitated moving away from the preconception of total conservation to instead adopt a renewed conceptual approach, one more specifically rooted in the site. The goal was to situate the proposal in time and embed it within a kind of cultural continuum, however specific it might be.

The project’s implantation establishes the groundwork for this dialogue. In an effort to preserve what remained stable from the existing structure, the foundations and masonry chimney of the former residence were retained, shaping a specific siting strategy. As a result, entry to the new building involves passing through the remnants of the old one—a kind of subtle act of remembrance, a duty of memory—which defines the arrival at the property. The secondary buildings on the site have been preserved and incorporated into the overall landscape design.