Beyond the city, trees are spared from the axe, left to age in tranquility. Here, time is counted in rings, and all things whisper through their marks. We met Daniel De Belder, who welcomed us into his garden—a tranquil suspension, a vessel steeped in time. This was one stop on our design study journey to Belgium in March. Spring had not yet returned to the woods — what met us first was its scent: damp earth, cedar, a hint of wood smoke. Here, no smell of industry lingers; only fragrances crafted not by man, but by nature itself.

Crossing the tidy courtyard, Daniel pushed open a aged wooden door. Light spilled like water from the high windows, outlining a still and silent world stacked with immense timber and his works. Outside lay an oil-green meadow and a bright yellow facade; inside felt like sinking into another time—where moments are suspended in quiet tenderness, and each piece of wood is held in deep slumber. Some works stand tall in quiet defiance, while others lean as if lost in contemplation. On their surfaces lie the ciphers of time: the stains left by years of water, the shadowy interlace of worm and fungus, or the grain softened by wind and drifting sand. “It feels like a cabinet of monsters,” Daniel remarked, a calm humor flickering in his eyes.

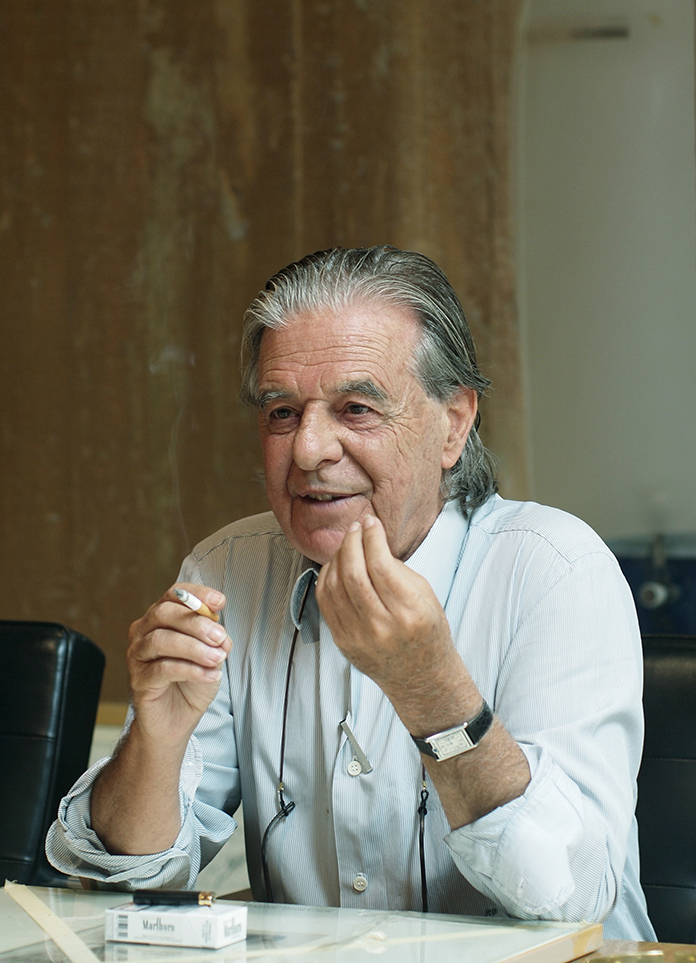

Daniel tends this woodland with care, letting the trees grow freely and taking only those lives ended naturally by storm, gravity, or the passage of time. Running his hand across the bullet mark on a stump, he said, “These timbers are not silent materials, but witness carrying a century of memory.” Most works retain almost the tree’s original form: a gnarled branch transformed into a staircase for his granddaughter to climb; a twisted trunk becoming a bench for rest. Others bear the revelations of fire and blade—the scorched cedar fibers turned translucent, refracting amber ripples when caught by the light. “Burning is not destruction, but revelation,” he said, his gaze lingering on the charred grain.